This is a work of nonfiction that reads almost like prose poetry brushing up against autotheory. Thematically, it moves through addiction and relapse cycles, but it’s not a recovery narrative, trauma porn, or redemption arc. I write from within collapse, where the self disintegrates and the form spirals, leaving no stable ground or resolution for the reader.

I lie on my sister’s couch, soaked in sweat, sadistically edged by anxiety. I teeter here for hours, like a tightrope walker who’s sobered up and found themselves suspended between the Twin Towers on a crisp autumn morning.

I count my inhalations: one, two. Then my exhalations: six, seven. I lose consciousness and my footing slips.

I still don’t know what happened. Did I seize?

I come to mid-freefall, gripped by terror as syncope gives way to full-blown panic.

I’m convinced that I’ve died, sentenced to wander some perverse purgatory for eternity.

My thoughts spiral into a recursive loop of delirium. I need to go somewhere to escape.

But where?

I pace neurotically. Where can I go? Where? I plead with my dissolving thoughts.

I hear someone at the door, fumbling with keys. The lock begins to turn.

This is it.

They’ve come to collect me, I think, sweating even more, waterlogged with hundred-proof perspiration.

The door creaks open. My sister stands there, holding two bags from the liquor store, one in each hand, pushing the door open with her foot.

I forgot about her.

The sight of those black plastic bags with their sleek gold accent slows the spiral just enough for me to grab a passing ledge.

I snatch them from her hands.

As I furiously suckle the Jameson, she looks at me with a kind of maternal pity — or is it fear? I can’t tell. I avoid her gaze and take a less desperate sip, hoping it buoys the humiliation pulling me under.

When I was young, I romanticized taking things to their limit, then beyond as I imagined a beautiful death. Or rather, I imagined the story of my death from the reader’s point of view, an impossible perspective.

I wanted to live where most only visit on weekends. My half-baked ideas steadied me as I stumbled towards a superficial self-annihilation. Let life overflow and drown me, I’d babble slurring my words.

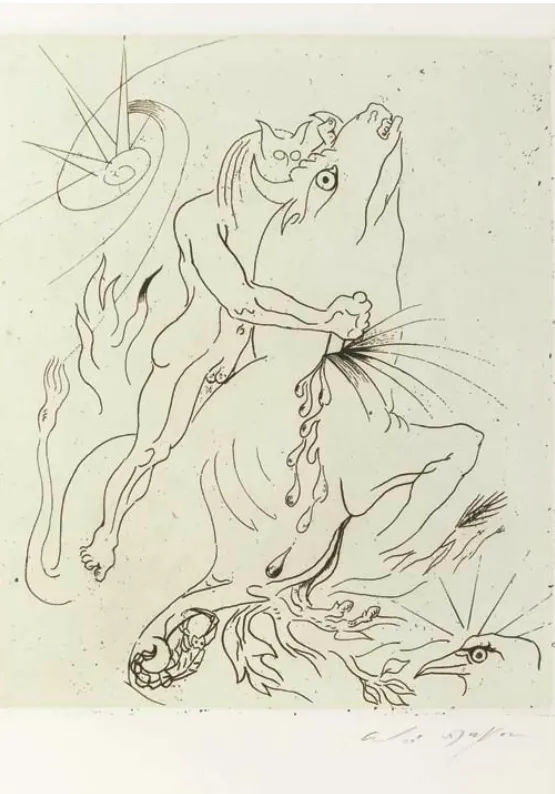

I’d disappear into Dionysian blackouts, inebriated by ritualistic consumption of Crazy Stallion malt liquor.

I could only expend so much before there was nothing left. My dignity was the first offering but it only whet the palate and I metaphorically awoke one day in a motel bathtub, jagged scar across my lower abdomen, still clutching an empty bottle of Xanax.

Back in East Harlem, I had all my organs but no Klonopin. My plug wouldn’t make the trip and I owed him six hundred anyway. The Jameson would have to do. Benzos treat alcohol withdrawal, so why not the other way around?

I later explained this junkie folk wisdom to the Physician Assistant during detox intake. She called it “crackhead science.” Yet as it sloshed in my fasting stomach, a thin relief crept in.

I set the bottle down and pick at the label with my chewed down nails.

“I think I need a hospital or something,” I said.

“Yeah, no shit,” my sister replied.

I drag my drunk ass to Mt. Sinai at six a.m., hoping to be one of the few admitted that day. Everyone there is drunk or high—there’s no other way to make it through.

On the seventh day I’m discharged, certain it’s all behind me.

Two days later I find a bottle of liquid etizolam1 that’s rolled under my bed.

The tape skips ahead and the cycle begins again.

Even now, I recall short flashes of excitement against a backdrop of cruel behavior and self-degradation.

It always started with that fantasy being bludgeoned to death by reality, only to be quickly forgotten.

As usual, I blacked out last night and can’t remember what I did. I always assume the worst, because more often than not, it is. I know I humiliated myself, but how? Was I an asshole to the bartender? They’ll never let me back. Maybe I sent dozens of texts to a girl I just started talking to. I can’t check because my phone is dead, and I’m too afraid to plug it in. Did I start a fight? I hope I didn’t spend the entire night berating my poor girlfriend.

My bed is wet. So are my pants, which I forgot to take off. I pissed myself again.

It’s the shame that gets to me. It feels like something burrowed in the pit of my stomach, a small marmot thrashing around. With nothing to eat, the bastard feeds on me.

I need to expel the fucker before it moves on to other organs.

No matter how much I try, or think about trying, I can’t make it stop. It gnaws and gnaws until I can’t take it anymore. I have to drown the little shit, so I reach for the closest bottle that still has something left. After a few pulls, it falls silent. My spiraling mind settles. It’s dead — for now.

But each day, it gets worse.

There’s a tendency to perceive addiction as deferred suicide, but that was never the case for me. No matter how bad it got, the thought of killing myself never crossed my mind.

At the worst of it, I begged vague deities for a few more years. I wanted to rub up against death’s leg like a slutty cat begging for detrital scraps. I needed to come as close as I could, to leer over the edge without falling in.

I’d force myself to sit on the ledge, nervously dangling my feet like some crazy-ass Russian urban climber perched atop a dizzyingly tall crane, frozen by a fear of heights, compelled by the thrill of my own terror.

I sit at the edge of my bed, trying to imagine the room I’m rotting in as some kind of interstitial space between the possible and impossible, suspended in shame and insufferable French theory.

At the limit is pure disgust vibrating with anguish — like being pinned down and tickled until you shit blood.

It’s a nauseating despair stripped of romantic melancholia, that leaves only festering confusion.

My bouts of lucidity taste like the whiskey I almost threw up but forced back down.

I just want to pass out.

I’ve become so ground down and puny that I no longer wish to be conscious, but I don’t want to die, either.

A deep, intoxicated sleep is the only reprieve.

I wake up panicked and sweating. I gulp down a Budlight Platinum that’s been sitting on my nightstand for days, maybe weeks, I’m not sure.

Is this the interstitial space: unhygienic neurosis, glazed in filth, oscillating between unbearable wakefulness and a desperate bid to suppress it? Where is the mystical tumescence?

My capacity of will has imploded, leaving only the gravitational pull of a will to nothingness.

I’m caught in a death spiral, a narcotic feedback loop.

All that exists now is an eternal recurrence: not eating, not showering, just drinking and passing out.

I resign myself to the lulling rot.

I tear the bed apart looking for my fifth of whiskey. Find it, behind the frame. Take a swig, roll back over and close my eyes.

I dream I’m falling. I’m tenderly rocked as I descend toward a shifting earth that retreats the closer I come. I observe myself wrapped in the soothing embrace of passing air, and want to aimlessly drift forever. A warm calm envelops me like shooting Valium for the first time. My stomach unknots. The vertigo fades and the tension pulling me eases. I’ve forgotten why I should be ashamed.

I slam into the ground. I lie sprawled on the sidewalk, bones jutting from mangled limbs. I feel a tear along the right side of my head, there’s a flap of scalp dangling over my eye, caking it with blood. I struggle to bring what’s left of my arm toward it, to place the chunk back where it should be.

The paramedics arrive and rummage through my pockets for an insurance card that doesn’t exist.

“He’s fucked anyway,” one says. “Call the coroner. At least he had twenty bucks.”

They flip a coin to decide who does the paperwork.

The loser grabs the clipboard and my irritated witness scrawls the final word.

I slip back into wakefulness.

Where has the time gone? It’s been bent and contorted through blackouts, smoothed over with benzos, shattered by panic. It all felt like the same stretch of time…until it disintegrated

I don’t know when it did, but I can feel myself firmly on the other side.

It’s like waking up in the morning after going out. The night before explains my contorted stomach and encroaching terror, but I’m confused and severed from it.

I’m here, stuck with the consequences of what I don’t remember, because the memories never formed.

I write in a futile attempt to reach back across but the words slip through my fingers and

r

o

t.

1Etizolam is a benzodiazipine not prescribed in the US but was popular on the “research chemical” grey market.